Context

- The Reserve Bank of India shared the report of an Internal Working Group (IWG), which was set up in February to look at, among other things, the impact of farm loan waivers on state finances. The report has shown how farm loan waivers dented state finances and urged governments — both central and state — to avoid resorting to farm loan waivers.

Details:

- Since 2014-15, many state governments have announced farm loan waivers. This was done for a variety of reasons including relieving distressed farmers struggling with lower incomes in the wake of repeated droughts and demonetisation. Also crucial in this regard was the timing of elections and several observers of the economy including the RBI warned against the use of farm loan waivers.

- The latest report of RBI has concluded: “The IWG recommends that GoI and state governments should undertake a holistic review of the agricultural policies and their implementation, as well as evaluate the effectiveness of current subsidy policies with regard to agri inputs and credit in a manner which will improve the overall viability of agriculture in a sustainable manner. In view of the above stated, loan waivers should be avoided”.

What has been the impact on state finances?

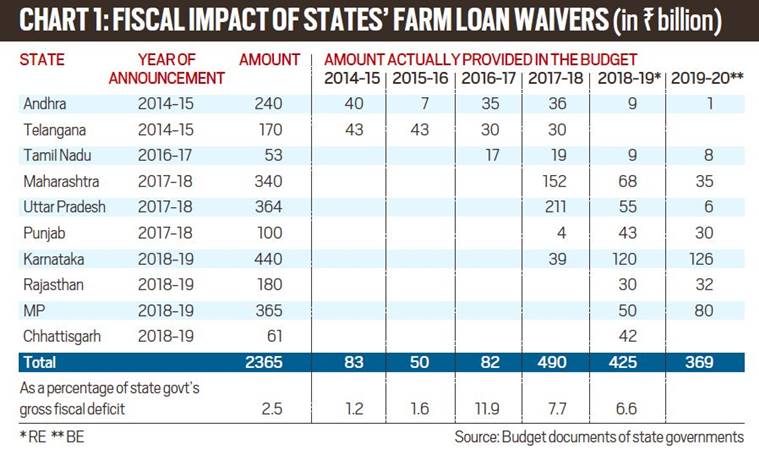

- Chart 1 from the RBI report details the impact on state finances in successive years. Typically, once announced, farm loans waivers are staggered over three to five years. Between 2014-15 and 2018-19, the total farm loan waiver announced by different state governments was Rs 2.36 trillion. Of this, Rs 1.5 trillion has already been waived. For perspective, the last big farm loan waiver was announced by the UPA government in 2008-09 and it was Rs 0.72 trillion. Of this, actual waivers were only Rs 0.53 trillion — staggered between 2008-09 and 2011-12.

- In other words, in the past five years, just a handful of states have already waived three-times the amount waived by the central government in 2008-09. The actual waivers peaked in 2017-18 — in the wake of demonetisation and its adverse impact on farm incomes — and amounted to almost 12 per cent of the states’ fiscal deficit.

What is the impact on economic growth, interest rates and job creation?

- In essence, a farm loan waiver by the government implies that the government settles the private debt that a farmer owes to a bank. But doing so eats into the government’s resources, which, in turn, leads to one of following two things: either the concerned government’s fiscal deficit (or, in other words, total borrowing from the market) goes up or it has to cut down its expenditure.

- A higher fiscal deficit, even if it is at the state level, implies that the amount of money available for lending to private businesses — both big and small — will be lower. It also means the cost at which this money would be lent (or the interest rate) would be higher. If fresh credit is costly, there will be fewer new companies, and less job creation.

- If the state government doesn’t want to borrow the money from the market and wants to stick to its fiscal deficit target, it will be forced to accommodate by cutting expenditure. More often than not, states choose to cut capital expenditure — that is the kind of expenditure which would have led to the creation of productive assets such as more roads, buildings, schools etc — instead of the revenue expenditure, which is in the form of committed expenditure such as staff salaries and pensions. But cutting capital expenditure also undermines the ability to produce and grow in the future.

- As such, farm loan waivers are not considered prudent because they hurt overall economic growth apart from ruining the credit culture in the economy since they incentivise defaulters and penalise those who pay back their loans.

So, are the states increasing their fiscal deficits or cutting capital expenditure?

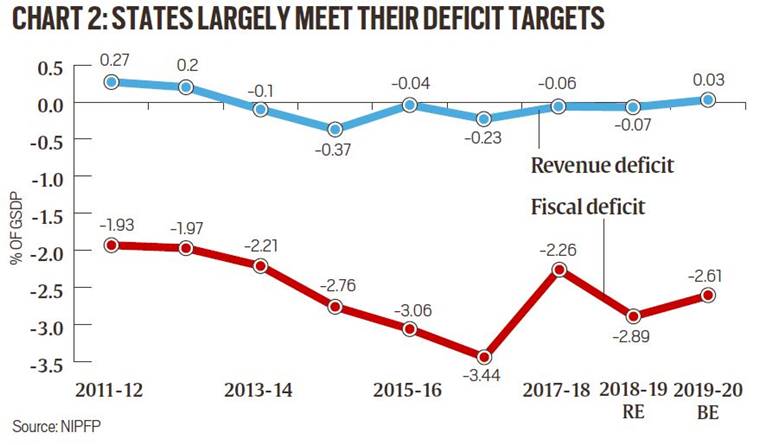

- There is no ready answer about specific states mentioned in Chart 1. However, an analysis of the latest state Budgets by the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), released last month, shows that, on the whole, notwithstanding farm loan waivers etc., state governments stick to their fiscal deficit targets. In other words, state governments are not as profligate as they are made out to be. As Chart 2 shows, states barring the episode (in 2015-16) when they had to absorb the losses of state discoms (power distribution companies) under the Ujjwal Discom Assurance Yojana (or UDAY), have stayed true to restricting their revenue deficit to zero and fiscal deficit to three per cent of their GDP.

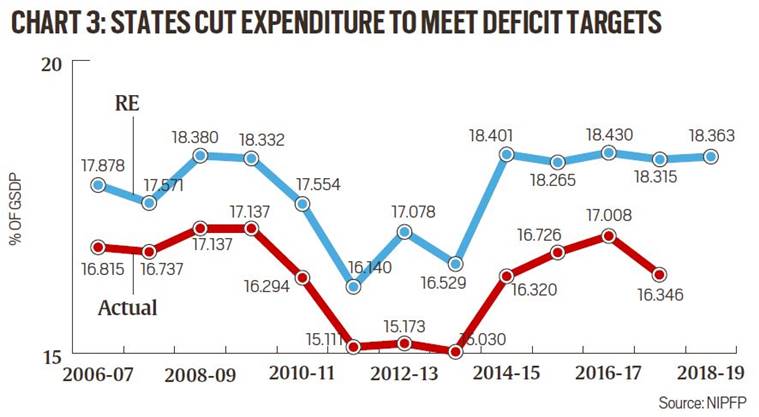

- But this relieving picture has a flip side. The way states meet their deficit targets is not by raising more revenues but by cutting expenditure. Chart 3 shows how, each year, the actual expenditure is considerably lower than the Revised Estimates (RE) presented in the budget. And within expenditure, as Manish Gupta of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP) points out, capital expenditure is cut relatively more than revenue expenditure.

How much do state finances matter for India’s macroeconomic stability?

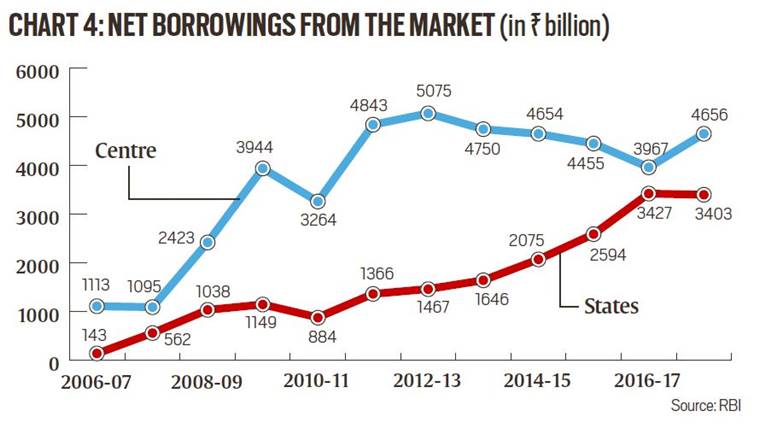

- Far too often, analyses of the Indian economy focuses on the Union government’s finances alone. But the ground realities are fast changing. The NIPFP study of state finances reveals that all the states, collectively, now spend 30 per cent more than the central government. Moreover, as Chart 4 shows, since 2014, state governments have increasingly borrowed money from the market. In 2016-17, for instance, total net borrowings by all the states were almost equal (roughly 86 per cent) of the amount that the Centre borrowed.

Source: Indian Express